By: Robert St. Martin

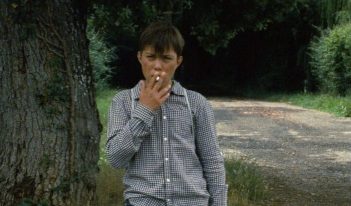

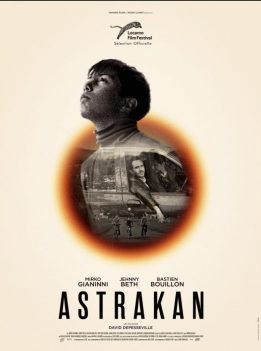

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 3/22/23 – On Sunday April 19, Acropolis Cinema featured a screening of David Depesseville’s feature-length debut film “Astrakan” (France, 2022) as part of the Locarno in L.A. Film Festival at 2220 Arts & Archives. David Depesseville explores the strangeness and confusion of growing up during the prepubescent period of life. “Astrakan” revolves around a 12-year-old orphan named Samuel (Mirko Giananni). Eventually, he ends up living with Marie (Jehnny Beth) and Clément (Bastien Bouillon), a young couple with two children of their own. “Astrakan” is a social allegory disguised as a coming-of-age tale imbued with the latent cringe cruelty of adolescence found in the films of Todd Solondz and French director Claude Miller. The film has been picked up for distribution by Altered Innocence and I hope it will have a theatrical run in Los Angeles.

Using religious imagery and child trauma, this French bucolic is a fusion of rustic and magical realism, a seemingly banal portrait of a family’s mishaps caused by a cognitive dissonance exposes society’s collective cognitive dissonance and the hypocrisies it has been running on and in raising the next generation. The film’s title of “Astrakan” refers to the highly prized soft black Astrakan lamb wool which is popular in Central Asia and Russia but actually comes from the unborn or newly born baby Astrakan lamb. Ironically the black lamb is the one sacrificed for its wool – and it serves as a metaphor for the young Samuel in the story. This is brought home is a supercharged dream sequence at the end of the film against the scoring score of “Agnus Dei” from Bach’s Mass in B-minor as Samuel is swimming in a lake with his foster parents picnicking nearby and astonishingly an orphaned black lamb suddenly appears.

Using religious imagery and child trauma, this French bucolic is a fusion of rustic and magical realism, a seemingly banal portrait of a family’s mishaps caused by a cognitive dissonance exposes society’s collective cognitive dissonance and the hypocrisies it has been running on and in raising the next generation. The film’s title of “Astrakan” refers to the highly prized soft black Astrakan lamb wool which is popular in Central Asia and Russia but actually comes from the unborn or newly born baby Astrakan lamb. Ironically the black lamb is the one sacrificed for its wool – and it serves as a metaphor for the young Samuel in the story. This is brought home is a supercharged dream sequence at the end of the film against the scoring score of “Agnus Dei” from Bach’s Mass in B-minor as Samuel is swimming in a lake with his foster parents picnicking nearby and astonishingly an orphaned black lamb suddenly appears. The kid’s unprocessed traumas manifest themselves in bodily (dys)function (he often clogs the toilet or soils his underwear) while navigating his budding sexuality. The tall girl next door in Samuel’s orbit takes an interest in him as a playmate but she is more sexually aware than Samuel. Due to the fact that they are both prepubescents, the lust-laced seduction initiated by the girl comes off as cringeworthy and awkward. Samuel is awkward in his dealing with boys his own age as well as fostering a strange fascination with his foster mother Marie’s good-looking brother Luc, who still lives with his own parents on another farm.

The kid’s unprocessed traumas manifest themselves in bodily (dys)function (he often clogs the toilet or soils his underwear) while navigating his budding sexuality. The tall girl next door in Samuel’s orbit takes an interest in him as a playmate but she is more sexually aware than Samuel. Due to the fact that they are both prepubescents, the lust-laced seduction initiated by the girl comes off as cringeworthy and awkward. Samuel is awkward in his dealing with boys his own age as well as fostering a strange fascination with his foster mother Marie’s good-looking brother Luc, who still lives with his own parents on another farm. In the midst of this vortex, Samuel tries to make sense of the senseless and perplexing, and somehow move forward. Despite his young age, Samuel appears hardened by his misfortunes and accepts his fate with firm stoicism, for the most part. Occasional outbursts by Samuel accompany the most extreme situations. It comes to a head when Samuel is forced to stay with his uncle Luc (Theo Costa-Marino), an implied pederast, or when he is beaten by his foster father after he is falsely accused of something.

In the midst of this vortex, Samuel tries to make sense of the senseless and perplexing, and somehow move forward. Despite his young age, Samuel appears hardened by his misfortunes and accepts his fate with firm stoicism, for the most part. Occasional outbursts by Samuel accompany the most extreme situations. It comes to a head when Samuel is forced to stay with his uncle Luc (Theo Costa-Marino), an implied pederast, or when he is beaten by his foster father after he is falsely accused of something. Defesseville does not even attempt to depict this brutal and evil scene in a conventional suspenseful manner. His disengaged perspective lets the act unfold naturally with lyrical realism and an anticlimactic denouement. If “Astrakan” had an allegorical precedent, it would be the narrative archetype of “Teorema.” In Pasolini’s classic, a mysterious character, The Visitor, disrupts the lives of a bourgeois family. The stranger acts as an agent of discord, discombobulating the family’s usual flow of events.

Defesseville does not even attempt to depict this brutal and evil scene in a conventional suspenseful manner. His disengaged perspective lets the act unfold naturally with lyrical realism and an anticlimactic denouement. If “Astrakan” had an allegorical precedent, it would be the narrative archetype of “Teorema.” In Pasolini’s classic, a mysterious character, The Visitor, disrupts the lives of a bourgeois family. The stranger acts as an agent of discord, discombobulating the family’s usual flow of events. Although “Astrakan” becomes an elaborate narrative on the surface but contains hidden layers that reveal themselves upon closer inspection. Its title refers to a special kind of black wool that comes from lambs killed before birth, and there is an inherent cruelty to the film throughout. As the story progresses, a lamb becomes a frequent symbol, amplified by the religious setting and Samuel’s preparation for his first communion. Despite conventions of the coming-of-age genre, Depesseville makes a clever play on the notion of black sheep and Agnus Dei to create an ambiguous character.

Although “Astrakan” becomes an elaborate narrative on the surface but contains hidden layers that reveal themselves upon closer inspection. Its title refers to a special kind of black wool that comes from lambs killed before birth, and there is an inherent cruelty to the film throughout. As the story progresses, a lamb becomes a frequent symbol, amplified by the religious setting and Samuel’s preparation for his first communion. Despite conventions of the coming-of-age genre, Depesseville makes a clever play on the notion of black sheep and Agnus Dei to create an ambiguous character.